- Home

- Andrez Bergen

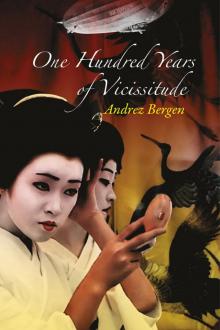

100 Years of Vicissitude Page 10

100 Years of Vicissitude Read online

Page 10

The woman spat out the pronoun, threw down her hands, and this time glared from eyes that glistened in the streetlight. I would have ducked for cover if there had been anywhere convenient.

‘I was lucky.’

‘Unquestionably. How so?’

‘Simple—Tomeko and I weren’t here. I wish I could say a book saved us. Rather, we were saved by a booking. Ta-dah.’

15 | 十五

First impression?

In Egypt, I once saw the conjoined statues of Ramses II and his wife Nefertari, and this pose was similar, except that the faces of the two marbles were female and identical—as if Ramses had been given a very public flick, and the queen inducted her mirror image to sit atop the throne beside her.

The statues were Kohana and Tomeko, seated with perfect posture next to one another on tall wooden chairs that were pressed up against a wall.

On either side of them was a set of leather-bound Encyclopædias Britannica, standing upright across the floor. People lurked nearby, mere silhouettes. Even so, I believe I could distinguish officers’ uniforms.

The girl to the right was dressed in a plain white kimono, the colour of snow. Her partner, on our left, wore a robe of fathomless black silk. Both had their white geisha masks identically applied, and their hair shone, with paraphernalia inserted.

There was a red strip of undergarment poking out a few millimetres above their kimono, making their throats look whiter. Neither moved. I barely made out their breathing, and the blinks were so discreet they would be easily missed.

‘Which one is you?’

My Kohana stood beside me, dressed far more simply. ‘Can’t you guess?’

‘Honestly? I have no idea. The one in black?’

She fidgeted beside me. ‘Why do you assume that? No, I’m the one in white. This was one of Oume-san’s gala gimmicks, a play on matching, inanimate bookends—with the twist being the opposing colours, and the books arranged to either side, not between. She also occasionally had us dress in identical kimono, but this was her favourite routine, one Tomeko and I regularly performed at functions while we were hangyoku. The guests delighted in it—they made a sport out of judging which one of us was which.’

‘Was there anything to give the game away?’

‘Only when we performed. Tomeko was the far better shamisen player; I was a marginally better tachikata, or dancer. Also, to the intrepid observer, the colours. White was always going to be Tomeko’s colour, and black mine, just as you presumed—though sometimes we exchanged the robes to keep people guessing. This was one such occasion.’

There was a sudden, piercing wail that began outside the room, far away. Other sirens joined it, closer by. The two bookends glanced at one another, terrified girls, their ethereal image shattered.

Then the lights switched off.

‘The same night the B-29s bomb Tokyo,’ Kohana said. ‘March 9. This is the booking that saved our lives. The very night Asakusa was levelled and we lost Oume-san, along with the rest of our slapdash family.’

I could hear a muffled thump-thump in the near distance, and the overhead chandelier rattled.

16 | 十六

Kohana looked wonderful as usual.

This bothered me.

‘Let’s say we flip proceedings,’ I decided.

‘Sounds fresh—I’m always up for that. Something different.’

‘Fine. How about describing what I wear, for a change?’

‘Why would I do that?’

I held up my hand. ‘Indulge me. I seem to go into a great amount of detail regarding your costume changes, whenever—and wherever—they transpire. Usually in places I don’t care to be.’

‘That’s because you’re enamoured with my wardrobe.’

‘Hogwash. Stop leading me astray—back to my question. Why don’t you have a shot at describing what I wear?’

She gave me a quick once-over. ‘What, a smoking jacket that’s seen better days and needs the left elbow mending, worn-out slippers, pants that don’t flatter your figure and are threadbare round the knees, and that charming, accidentally off-colour cream cravat?’

‘Exactly. It doesn’t change.’

‘Of course it does. The outfit gets more tatty.’

‘Ahem. Hardly fair. You know Fred Astaire was buried in a smoking jacket?’

‘That’s news to me. I liked his movies with Ginger Rogers.’

‘I thought they would be your vintage—my grandmothers’ generation.’

‘Oh, Wolram. You like to decry “Frenchie” fashion designers, but were you aware that the smoking jacket on your back right now was designed by a Frenchman?’

‘What? Nonsense.’

‘Believe me, it’s a classic Yves Saint Laurent. Why not check the label? I met Yves Henri, you know.’

‘I wouldn’t care if you met Napoléon Bonaparte.’

Try as I might, I couldn’t rotate my head enough to see the tag, not while I was wearing the thing, and I did not want to give this girl the satisfaction of espying such doubt.

The smoking jacket had been a Christmas present from Judy—my secretary, remember her? She knew my anathema for things French. Why would she gift me something designed by one of these people? A smile, smug on the rear-end of mischief, worried me.

‘This was when I went to Paris in 1965,’ Kohana trawled on, oblivious, ‘to rendezvous with my friends Chimei Hamada and Kenzo Takada. Yves Henri and I became avid pen pals—until I told him that his pantsuit design was one of the ugliest things I had ever laid eyes on. Even so, he dressed Catherine Deneuve in Buñuel’s Belle de Jour, so you have sizeable shoes to fill.’

She tilted her head.

‘Of course, you really don’t have to believe me—perhaps you should consult your grandmothers.’

I felt bruised. This woman didn’t just fight with kid gloves; she used them to bludgeon one’s senses.

‘My kingdom for a dry-cleaner’s and an Italian shoe store,’ I muttered as I peered at her. ‘You don’t happen to have any men’s clothes in that excessive closet of yours? It seems to have a larger capacity than the Magic Pudding’s.’

‘I’m sorry.’ She gifted me a saccharine expression. ‘None that would fit—and nothing to match those Jolly Roger boxers of yours.’

‘Desist,’ I warned her. ‘We’ve already aired that dirty laundry. Shall we move right along.’

‘Aye, aye, skipper,’ she saluted, damn her. ‘Anyway, aside from your dress-sense, Wolram, could you tell me one thing? How long did it take you to cultivate this image of yours? You know, the smoking jacket and cravat, and the plum in your mouth?’

‘Eh?’

‘The “My dear” this, and “Good Lord” that, ad infinitum.’

‘What are you gabbling about?’

‘Well, it’s hardly genuine, is it?’

‘How do you mean?’

‘You know precisely what I mean. A sham.’

‘Oh,’ I chose my words carefully, ‘you noticed.’

‘It’s pretty obvious.’

I grinned in a manner that I prayed touched upon predatorial élan. There was an image to uphold, but I had no mirror to check.

‘Brownie points there, my dear. The process took a few elocution lessons. Years of them, to be honest, but I persevered. I couldn’t lead the world while sounding like an uneducated oaf.’

‘The greatest leaders are honest ones,’ Kohana said.

‘An airy fairy ideal, to be sure.’

‘You went to university.’

‘Yes, but I sounded colloquial, too kitchen-brand, working class “Aussie”. People respect those who use words they cannot understand.’

‘Really? I thought they laughed at them.’

That made sense. Damn. Why hadn’t the simple thought ever occurred to me? ‘Perhaps that’s why my political career never got off the ground?’

17 | 十七

‘So, as I mentioned, this particular night, Tomeko and I were two miles away, entertaining military clients

the way we did most often during the war—together. Not a single bomb hit the street where we kicked off our okobo, and the fires blew in the opposite direction.’

The two of us were in the Asakusa street again, entertained by a chorus of bees that had become a monotonous drone—more like cicadas in high summer. They were a season early, but just as distracting.

Kohana was considerate enough to allow me use of the couch, but I felt unsettled. ‘There were winds?’

I looked round at all the clapboard buildings, stretching out along both sides of the road. Ready-made kindling. Why weren’t there brick buildings?

‘In an earthquake-friendly country like Japan? Wood and paper were safer.’

‘Surely you had air raid defences around a city as vital as Tokyo.’

‘We did, but this was 1945. The country was exhausted and most of our best soldiers were dead, missing, or fighting elsewhere. The raid happened at night, which made things more difficult, and the B-29 pushed the throttle to three hundred and fifty-seven miles per hour—making it faster than our fighter planes, such as the Mitsubishi A6M Zero.’

‘The same plane Y flew into that ship?’

‘Mmm.’

The girl sat down on the sofa. I looked at the alley not so far away. Surely, it would be quieter there. I could feel a breeze starting to gather.

‘No, don’t go there. Sit here, with me.’ Kohana patted the leather.

‘I don’t want to.’

‘Are you being pedantic, my sweet?’

‘Don’t call me that. I’m not your sweet. I would like to go home.’

‘Home?’ She laughed out loud. ‘Where on earth is home? Do you mean my “hovel”, those shacks out in the Hereafter, or some place more luxurious back in Melbourne?’

‘You’re an evil woman.’ I scowled.

Kohana absent-mindedly fiddled with the odd accessories in her hair.

‘Perhaps you’re right. I do often wonder. Am I?’

I refused to say a word.

‘In this instance, I can see both sides of the equation. The American fliers didn’t get off scot-free. Forty-two of their bombers were heavily damaged, and most of them returned to base with blistered paint beneath. Fourteen B-29s crashed; two hundred and forty-three US airmen were lost.’

‘Stop it,’ I muttered. ‘Just stop it with the facts and figures. I’ve heard enough.’

‘You think so?’

‘I know so.’

‘But I have only a few more to share. Some of the stats are interesting.’

‘How?’

Kohana misunderstood that I was registering disbelief, and set about explaining ‘how’ she found the folly intriguing.

‘Well, while some planes were shredded by flak, several had non-combat related technical problems, and one aircraft was actually struck by lightning. Vortex updrafts from the fires tore the wings off one bomber. A B-29, nicknamed “Tall in the Saddle”, crashed in Ibaraki—killing nine crew-members. Three survived. One of them was executed by the military police, and the other two were interned to Tokyo’s military prison, where they burned to death in another air raid.’

Kohana breathed out heavily.

‘I’m not going to sit here and tell you that the men in these bombers did wrong. There were too many diabolical feats during the war, enacted by both sides.’

To be honest, I wasn’t paying the best attention. I’d almost finished my drink, had tried to blot out most of her diatribe, and was distracted by the reverberation in the air. I felt exhausted and overwhelmed. I sat, with brutal finality, next to the woman.

‘There was a certain amount of evil adrift in the world, and some individuals channelled it more effectively than others.’

‘I know.’ More than she knew.

‘In this case, I’m thinking of the man who organized Operation Meetinghouse.’

‘Douglas MacArthur?’ I guessed, lacking enthusiasm.

‘No, but one day I’ll have to tell you about the time I pinched Douglas’s famous corncob pipe.’

‘You were on a first-name basis, yet still stole one of his accessories?’

‘Your grandfather Les asked me for a souvenir.’

‘He did?’

‘He did.’

‘And that excuses everything?’

‘Well, when I had my chance—puff! Gone. But not forgotten. The general had another dozen stashed in his quarters. He replaced it in minutes, and was tamping tobacco, then lighting up, as per image.’

‘Douglas MacArthur? Did you—’

‘Sleep with him? No, I was still undefiled then.’

‘Far too enlightening.’

‘Douglas preferred a quiet smoke and chat. I had a better grasp of English than most other geisha, so we met on some occasions. I found him kind of sad and lonely.’

I’ll admit to being flustered. ‘But he’s the one who organized the bombing?’

‘I said no, already. It was American Major General Curtis LeMay.’

‘I haven’t heard of him.’

‘Lucky. Did you ever see the Kubrick satire Dr Strangelove?’

‘A long time ago.’

‘The gung-ho character of General Buck Turgidson was based on LeMay. I read something he said to his crews before departure on this mission: “You’re going to deliver the biggest firecracker the Japanese have ever seen.” This is the same man who, in the 1960s, turned his bombing attention to Vietnam and recommended the use of nuclear weapons there. Our Japanese government saw him in a different light. On December 7, 1964, with much pomp and ceremony, they conferred the First Order of Merit, with the Grand Cordon of the Rising Sun, upon General LeMay. A reward for fine service.’

I could barely hear her now. The buzz had become a relentless roar.

‘So this LeMay was an evil man, and the Japanese officials were cowards. So what? Please, Kohana, shouldn’t we now beat a path away from here? I believe I’ve seen and heard enough. I listened to your rant. You must have had your fill as well.’

She took my cup from my hand, sipped, and gave it back. I looked at the trace of cherry red on the rim, and then investigated her face.

There was no fear.

‘This time, I’m staying,’ she said. ‘I need to be where they were. Where my real family died.’

‘I can understand your feeling guilt—it’s a survivor thing. But you have to close that chapter and move right along. Personally, I’d prefer to evacuate us—or I can go, you can stay. Be my guest. Just tell me, how do I get the Hell out of here? For God’s sake. Do you understand what I’m saying?’

I was raving. Why? Think utterly terrified.

Here I was, already a dead old man, terrified of what was about to happen. I could not begin to picture three hundred Superfortresses crowded together, in one sky, at the same time.

I pored over the black heavens, taking in the searchlights that swept to and fro, darting in and out of low-flying clouds. Straight after, I polished off the saké.

At the very least, I’d stopped whining and grown a balsa wood backbone. Thank blazes for the alcohol. I could feel my eyes were far too wide.

Kohana took my hand in hers. She smiled.

‘Be brave.’ Her voice steadied me. There was a degree of affection that soothed my nerves, rather than smothered them. When had that changed? ‘And thank you for being here, at my side.’

‘I don’t think I have a choice,’ I managed.

‘Hush. Don’t ruin the moment. What are you afraid of? We’re on cheat-mode—a little bombing won’t harm us.’

Straight after, I heard the payload whistle of three hundred-odd B-29s, and the air pressure switched.

18 | 十八

Which was when we ended up in a minimally decorated reception room, with the soundtrack of sirens and explosions at a safer distance.

I was standing up, but I had to fling out a hand to stop myself stumbling, and with that leaned against a wall. My heart was pounding.

‘Wolram, are you all right?

’

‘I’m fine.’

I hung my head for a while, steadying the old nerves. When I finally felt up to it, I straightened and patted Kohana, who was right beside me, on the shoulder.

‘Don’t worry about me. It will require more than three hundred bombers to take me out of the picture this time around.’

I expect the quip made her happy. She had on a plain white dress that reached just above the knee, and it looked like something my mother would have worn back in the late ’60s. I wondered if this was the intention—to inject something reassuring for me, a fond sensation, after the recent histrionics.

‘What’s happening now?’ I asked. ‘Is it the same night?’

‘Same night, same ongoing drama, I’m sorry to say. A different perspective. Are you up for more?—or need a rest?’

‘No, no, it’s okay. Given you lived these experiences, I’m thinking that playing the inactive ghost is not so terrible. Lead on, Macduff.’

‘We don’t have far to go. Look.’

The room was dark.

A group of nearly transparent people had formed a ring around two far more substantial girls, dressed in polar-opposite black and white kimonos that were decorated with geisha regalia. The teenage Kohana and Tomeko.

The girls were identical, each wrestling with her mirror image. The one in white pulled herself free, and slapped her sister—hard.

‘Get your hands off me,’ she hissed. ‘I’m going back there, to see if I can help.’

The other child held her cheek, which looked pink under the heavy white greasepaint. ‘It’s too dangerous,’ she warned. ‘There’s nothing you can do; the sirens are on!’

‘Kutabare!—Drop dead! You can play the coward, a role you’re made for.’ The fleeting look, from the girl in white to her partner in black, was a venomous one.

‘Tomeko tried to stop me,’ Kohana said at my elbow.

‘Apparently.’

‘I ignored her.’

‘That is one way to put it.’

‘And I ran all the way over.’

‘All the way, where?’

‘To Asakusa. The air raid. We were here, at this function, when it happened. I think I told you. As soon as the sirens started up and we heard the explosions, I made up my mind to go straight back to our okiya.’

The Condimental Op

The Condimental Op Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa?

Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa? 100 Years of Vicissitude

100 Years of Vicissitude