- Home

- Andrez Bergen

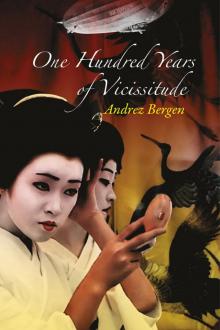

100 Years of Vicissitude Page 6

100 Years of Vicissitude Read online

Page 6

The girl watched me as she spoke. While there was not a single moment that her gaze failed her, I experienced doubt all the same. Probably it was the amount of detail padding out the sentence. I wouldn’t have been surprised had she rehearsed the disavowal.

I glanced at her likeness, seated beside us with the ironing board posture.

The fan in her right hand occasionally spread its wings to send a cooling breeze across an absurdly pale face. I studied those made-up eyes as she attended her pilot. I don’t care how well someone is trained to behave in a certain way, no matter if they’re a geisha, an actor, a politician, or a high-stakes businessman—the truth is always there.

When I looked back to my Kohana, there was a similar glint.

This glint was minute, cleverly hidden behind trapdoors and pulleys, and I’ll admit it was more difficult to smoke out. But in the end, I could see precisely how she felt.

‘You’re still in love with the miscreant,’ I said, affixing a degree of venom that surprised me.

4 | 四

I snapped to, on a toilet.

It was a well-appointed commode, to be sure, with a warm seat and a device attached called a Washlet S-1900—though I couldn’t read the instructions beside each button, as they appeared to be written in scrambled Japanese.

This remote controller also had the word ‘TOTO’ printed on it in Roman capitals.

Beside me, there was a roll of floral-pattern double-ply toilet paper hidden under a lace doily, just like the ones my grandmother used to crochet. Marcel Duchamp’s cistern this was not.

To be honest, I have no idea if I had relieved myself. Despite my quip to Kohana, I could not recall a prior necessity of doing so here in this limbo—but I was open to change. Perhaps the lavatory break was also designed to remind me of my infantile choice in undergarment. Several white, grinning skulls on black flags peered at me with undisguised mirth.

I hastily pulled up my pants, worked out how to flush, and then washed my hands at a nearby sink.

Kohana’s cabin was empty. Even the fire had scarpered. I walked the length of the living space, listening for some sign, but all I could hear was the wind whistling outside. It was like the set-up to one of those chilling Hammer films from the 1960s, right before Frankenstein’s monster barged in.

Annoyed, I went to the door and swung it open.

It was bright out there, with no breeze at all. Curious. I found my slippers by the entrance, slid them on, and walked out into the warmth.

I found my hostess seated on a grassy knoll, over near the edge of the cliff. She’d changed into a cotton robe with spacious sleeves, pink and grey and decorated with lotus flowers. There was a taut, saffron-yellow sash tied round the waist. The bun on top of her head had been unravelled and the straight hair now hung down past her hips. She also had a fringe that sat at a charming, minimal distance above the eyebrows.

Otherwise, the woman had her elbows on her knees and her chin in her hands. She was staring out over a sea that was much calmer and had a blue tinge to it.

In absent-minded fashion, I broke off some honeysuckle leaves from around the hazelnut’s trunk.

‘Don’t do that,’ Kohana said, without looking over. ‘There’s already enough love lost in the world.’

I didn’t reply, possibly because there was nothing to say to something so harebrained. I dropped the leaves in exaggerated fashion, looked around at the emptiness in all directions, and decided to mend some fences.

‘Would you overly mind, if I sat with you?’

‘Not really. No, not at all.’

Kohana edged over, in order to allow me space to unravel my old body into a reasonably comfortable position beside her. I believe I was getting used to the lack of chairs.

‘You have flowing water here. Where does that come from?’

‘The pipes?’ I could not tell if she was being glib.

‘Well, that’s apparent. And where do those pipes get their supply?’

‘I haven’t the foggiest.’

‘There’s a surprise.’

‘We’re really lucky this isn’t Yomi, a gloomy underworld—like Hades—that we learn about in Shintōism. Here, we have a view. A sky and an ocean to ponder.’

It was a splendid view. I decided to shut up and enjoy the moment.

To be fair, I was also trying to shake the sounds of the screaming on board that wartime ship.

Within moments, I had my limbs composed identically to Kohana’s and gazed over the sea to the hazy point where the horizon should have been. Of course, I couldn’t remain silent for long.

‘I have to mention something. You can desist with all the references to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘The toilet: Toto. The scarecrow back there, the allusions to the animals from Oz that are littered throughout the house, numerous other hints. I’m not myopic. I have noticed.’

‘Fascinating. Toto was once a famous toilet manufacturer in Japan—the name is an abbreviation of the two words making up the company’s name, Tōyō Tōki.’ She wasn’t looking at me. ‘I’m not the type to pay homage to a book I never picked up. Yep, I’ve seen the movie The Wizard of Oz—who hasn’t?—but it didn’t leave a lasting impression. Either you’re reading too much into matters, which I find dubious, or you brought baggage with you.’

I remembered the toilet roll doily.

‘Ahh.’

I rubbed my forehead. I thought I smelled a combination of salt and kelp in the air, but couldn’t be sure. It might have been the scent of a spit-roast.

The girl was right. Nothing here was what it appeared to be—and that, as sure as punch, put a spin on things.

5 | 五

‘I was born on Black Thursday.’

‘Oh, indeed?’ I scratched my chin, beneath the straggly beard.

‘You know it?’

‘That depends. If you are trying to frighten me, it’s not working. Black Thursday—boo! I’m tempted to toss a “humbug” right back.’

‘You’re peculiar. I’m not trying to scare you. Black Thursday was on October 24, 1929. The first day of the Wall Street Crash in the United States, and the beginning of the Great Depression.’

I seized the moment right after the girl finished giving her pint-sized speech to return a warm round of applause.

‘Wonderful! What a way to recall one’s birthday. It’s highly unlikely friends and relatives could forget a date like that, by gosh. In my case, I was nowhere near so fortunate. I shared my birthday with Armenian Independence Day, on the 21st of September, and wouldn’t be able to point out Armenia on a map.’

Kohana had her eyes fixed on the placid water far below. What she thought, I couldn’t tell, and to be honest I did feel the tiniest amount chastened by her silence.

‘Oh well, I must apologize,’ I ventured. ‘Did that rain on your parade?’

In answer, the woman ignored me.

‘I was not born alone,’ she took up, acting as if my babbling had never transpired. ‘I arrived four minutes after my sister. And the only thing that crashed for us on that date was our mother’s uterus. Seconds before, I had no name, and my mother was alive. Then, my sister had a twin. I came out screaming, and my mother’s womb collapsed. She died giving birth to me.’

‘Yes, I see.’ I felt a minor chill. ‘I do get your point.’

Spread out, on the sandy lawn beside us, was a thin mattress on which a dead woman lay. Of course, I recoiled.

The skin around this woman’s bare chest and neck had an ashen tinge to it, but I could not make out her face, since it was shrouded beneath a mess of black hair. The lower half of her body was covered with a quilt drenched in blood and sweat. Two lively, naked, screaming babies lay next to the woman.

‘Really, Kohana, this is too much. If you want an apology for my impertinence—you have it.’

I looked away, but after some seconds passed, I sneaked another glance at the diorama. It had packed up things and

vanished. I assumed I had to make a comment of some kind. My remaining semblance of good manners demanded it.

‘So, you had a twin sister.’

‘I did.’

‘Did you look the same?’

‘Are you asking if we’re identical? Yes. On the outside. But our innards were cast in completely different foundries—she had my mother’s healthy ones; I often think I inherited her dismembered, post-natal self.’

‘Eloquent? For sure. Far-fetched? Extraordinarily.’

‘Most likely you’re right.’ Kohana examined her lap and used fingers to smooth out the material of her dress.

‘I suppose death in childbirth was a far more common occurrence back in—when was this? 1929, you said? Ancient times?’

Again the girl ignored me. This was getting to be a diabolical habit.

‘My father refused to be called “Papa”. He held to the more formal Oto-sama, and he regarded me with an expression that said “You killed my wife”, or something close to it.’

There was no poignant, carefully choreographed picture-show this time. To all appearances, Kohana preferred to keep the old man out of frame.

‘How does one do that?’ I asked.

Deathlike silence, like talking to a wall.

‘Excuse me?’

‘Hmm?’ The girl looked over.

‘Aren’t we having a discussion here?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Then how does one do it?’

‘Do what?’

‘My original question, of course—devise a facial bearing that conveys so much? It would be rather useful. The poker face was a breeze for me to master, but I’m certain I could have closed the odd engaging business deal, with a filicidal scowl.’

‘I doubt it’s something you can flip on and off.’

‘Surely there’s a switch?’ I meant something emotional, but the woman went off tangent for material.

‘Wolram, my father wasn’t a power point.’

‘Do tell.’

‘But now I think of it, he had only that one expression—sustenance enough for the remainder of his life. Yes, the switch was left on. That would make Mama fortunate. Not only did she escape an exceptionally negative marriage partner and a brace of clutching kids, but she was in good company.’

‘How so?’

‘She relinquished life on the same date Christian Dior did in 1957—though I’ve heard tell that this is debatable. May I use your word? Scuttlebutt has it Dior died on October 23, not October 24 as reported.’

I honestly didn’t care one jot which day Dior kicked the bucket. I feigned interest for a couple of infuriating seconds, and then gave up. Bad enough that she’d tarnished scuttlebutt’s good name.

‘What does some Frenchie fashion designer have to do with your mother? Unless I’m missing an elemental clue here? If so, pray enlighten me.’

Kohana refused to answer, and I couldn’t tell whether this was because she was being truculent, or just damned well depressed. Either way, it made me irritable, so I turned my attention elsewhere.

‘There are no seagulls here,’ I muttered. ‘In fact, I’ve seen not a single bird since I arrived. Aren’t ravens and crows and other carrion supposed to be signifiers of death? All we have are those ibises on the kimono in there.’

I shifted in my squatting position to place my hands on my thighs. My lower spine was aching—an old complaint I’d come to term ‘art gallery back’, principally because I suffered it at insufferable exhibition opening parties.

A cold, gusty breeze had started up and I spied white tips on the waves below. Despite its non-committal nature to this point, the weather looked like it was about to turn brutish.

‘Shall we go indoors?’ I had in mind velveteen pillows and warm saké.

As I pushed to my feet, I could have sworn I heard the old bones creak. Once I’d achieved the amazing, I looked down at my hostess, but she hadn’t moved a muscle.

Her choice. I shelved any plans of playing it suave and walked unsteadily back to the hovel. Once I reached the door, I took off my slippers and went inside.

Somehow, the fire in the centre of the room had restarted and it gave off enough light to see by—if you didn’t mind a stubbed toe.

I felt hungry for the first time in an eternity, ravenously so.

I popped over to the pantry against the wall, the one where the rice crackers lived, and searched for a treat. There was a bar fridge set into the woodwork beside it, and inside that I discovered perfection. Sushi. A whole platter of raw fish of various colours, assembled purely for my satisfaction.

I took out the plastic tray, placed it on the table, and snapped apart a convenient pair of wooden chopsticks. I had no idea where to find soy sauce, but the situation offered deficient impediment.

Without further ado, I dug in—or gave it my best shot, anyhow. One chopstick strained, and then snapped, while the other slipped from my unprofessional fingers. I do believe I swore out loud.

‘What are you up to?’ Kohana asked from the doorway.

‘Trying my best to look competent.’

I picked up the stray chopstick, wondering whether I should give it a rinse, or go with the flow. I doubted bacteria would indulge in an afterlife and tried to use the utensil as a scale-model harpoon on an enticing chunk of orange—the salmon—beached atop a bundle of white rice. The devil was hard like leather, and I had all the competence of Captain Ahab.

‘You do know, that’s plastic?’

I stopped mid-lunge, to glance at her. ‘What do you mean, plastic?’

‘It’s fake. Made at Kappabashi-dori, a place we call Kitchen Town, near where I used to live in Tokyo. They specialized in realistic plastic display food for restaurants—like the sushi.’

‘Then why the blazes do you have it in your refrigerator?’

Kohana shrugged. ‘Where else would I put the thing? I don’t exactly have a restaurant, and it looks out of place on the secretaire.’

I thought this over for a moment. ‘True.’

The girl waltzed my way, whisked from my hand the counterfeit cuisine, and placed it back on its shelf in the fridge. ‘Are you really suffering from an empty stomach, or just bored?’ I heard her ask.

‘How could I ever get bored, my dear, with all the surprises you keep dropping off in my lap? It’s busier here than a department store bargain sale.’

Openly yawning, I leaned over so I could better see the framed photo of the military man and geisha that was propped next to the altar.

‘You and your inamorato Y,’ I deduced at this closer angle—but then checked myself. ‘Just a moment. How do I know the girl in the picture is you? Didn’t you just mention an identical twin?’

When I looked to my hostess, the doubt was hardly abated.

She had her head tilted to one side and gazed at me with a fathomless expression. One could imagine dropping depth charges there and never hearing them explode. Being reminded of the sham sushi, the whole package struck me as unnerving.

‘There’s a fine question,’ she said, at last.

Ill at ease, I returned my attention to the photo.

‘So, now we potentially have three people who all look the same—this is bound to become confusing. Or is this fake too?’

In the photo, I noticed a classic Japanese triple-storey villa on the other side of a pond behind the couple, and even in monochrome it boasted an unnatural iridescence.

‘Kyoto, right? I believe I recognize the building.’

Kohana had sidled up next to me.

‘That’s Kinkaku-ji and, yes, it was in Kyoto. It’s likely you remember the place from a computer wallpaper image that once popped up everywhere—you’re old enough for that. But, like the sushi you were poking just now, the building in the wallpaper was a phony. The one in this photograph is real.’

You’re losing me.’

‘I suspected as much—hang in there, tiger.’ Kohana smiled one of her big, rich numbers, and I felt my l

egs go unsteady. She knew how and when to allocate those prizes.

‘You really are dangerous,’ I grumbled.

The girl winked at me. ‘Deshō?’

‘What?’

‘Deshō—um, how do I put this? Deshō has many meanings, usually things like “right?”, or “isn’t it?”; it’s used as a confirmational tag, for agreement, or when one isn’t sure. In this case, I was agreeing with you.’

‘Well, yes, whatever.’

‘Deshō.’ She laughed to herself. ‘Getting back to Kinkaku-ji, let me also explain that a little clearer. You do know the twentieth-century Japanese writer Yukio Mishima?’

‘One Q&A I can tackle, with complete conviction—he killed himself via ritual suicide, am I correct?’

‘Seppuku. That’s right. Kudos, Wolram. How did you know?’

My invisible victory punch fizzled in midair. I ought to have been accustomed to that.

‘Denslow, again. Remember the Japanophile? He always had his nose in a book by some Japanese author. Mishima popped up. One of his favourites, he said, when we were sharing a cup of tea and the conversation was flailing.’

‘Did you look at any pages inside?’

‘No need, my dear. I answered your question. Deshō?’

Kohana looked dubious. ‘Delightful. Mishima penned a famous novel called The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. You wouldn’t have heard of it.’

‘Sorry. Not on any of my reading lists.’

‘Don’t worry, I assumed as much. The story revolves around a mad monk who adores beauty—yet, at the same time, loathes it—and he ends up setting fire to one of the most beautiful buildings in Japan. A place that, until then, had survived six hundred years, some particularly violent centuries. Mishima based the novel on real life. Kinkaku-ji burned down in 1950, and was rebuilt in 1955. The building on the Apple wallpaper is the remake, but in the photograph here, you can see the original.’

‘Which you visited? Or was it your sister?’

The Condimental Op

The Condimental Op Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa?

Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa? 100 Years of Vicissitude

100 Years of Vicissitude