- Home

- Andrez Bergen

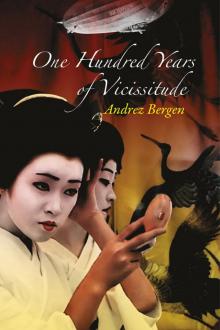

100 Years of Vicissitude Page 8

100 Years of Vicissitude Read online

Page 8

‘I think all gods can do the comb trick. He then ordered a barrier built around the house, in which there were eight gates. At each gate, a cavernous tub is placed upon a bench, and the eight tubs are filled with eight-times-filtered saké.’

I noticed that one of the beastie’s heads, on Kohana’s right shoulder, was split in two, with a raised scar of about four centimetres between the eyes. I stopped massaging and, with care, touched the area.

‘What happened here?’

‘A story for another day,’ Kohana said.

‘You and your secrets.’

‘A girl has to keep some things under the cuff.’

‘I have grave reservations about that.’ My fingers were aching, but I said nothing. I doubted she’d let me off the hook.

‘Fair enough. So, as I was about to tell you, when the beastie makes his lumbering eight mountain/eight valley arrival, he finds his path blocked and, after much huffing and puffing—like the wolf in the three little pigs story, really—Orochi finds that he can’t breach the barrier.’

‘Baffling.’

‘Very. To make matters worse, Orochi’s acute sense of smell takes in the saké, which the polycephalic dragon loves—like you, really. So, the eight heads entertain a dilemma: they desperately want to guzzle the delicious saké that calls out to them, much like the Sirens from Homer’s Odyssey, yet the fence obstructs their path, blocking any easy access to reach the precious booze.’

She stopped, and groaned.

‘Too hard?’ I ceased with my pressing.

‘No, no, perfect. Don’t stop.’

‘Could you keep the groaning to a minimum?’

‘Oh you.’

‘Story.’

‘Well, when one head suggested they simply smash the barrier down, the consensus was that this would knock over and waste the saké.’

‘I don’t think it needs a consensus to work that one out.’

‘He is a beastie, remember. When another head proposes they combine their fiery breath and burn the fence into ash, they agree that the nihonshu would potentially be evaporated.’

‘What was the temperature of the saké?’

‘Not part of the tale—deshō? As Orochi looks closer, he finds that the gates are actually unbarred and, pining for the saké on the other side, his heads are keen to stick their necks through to go guzzle it. But here the eighth one, which is the smartest, warns his cranial brethren of the folly of such action—then volunteers to head through first to make sure the coast is clear.’

‘I’m not sure if that’s brave, selfish, or downright stupid.’ My thumbs, smarting as they were, found a knot, and I focused on that.

‘Ouch! No, no, don’t stop. Good pain. Of course, it’s a cruel trap, as Susanoo skulks in some shadow, hiding, and allows that single head to drink the alcohol in safety. The head, buzzing by now with the carefree abandon that saké imparts, reports back to the others that there is no danger. With a “Whoopee!”, all eight noggins plunge through a different hatch, greedily skulling every last drop in the vats, and then revel in the effects of the drink.’

‘That, I can imagine.’

‘I’m sure you can. Alas, it has a sad finale. As the heads reel, Susanoo launches his attack. Drunk from slurping too much saké so quickly, the great serpent is no match for the wily, tee-totalling hero, who decapitates each dazed crown in turn and thereby slays him—a fitting lesson for all eight-headed beasties out there with a taste for the hard stuff.’

‘Was this hero of ours wielding a sickle, or a sword?’

‘I really don’t know.’

‘Sounds like Orochi could’ve done with some lessons from the Lernaean Hydra. Eight heads are not so useful if they don’t grow back.’

I took my hands off Kohana’s shoulders, and leaned back.

‘There. Penance paid for my stupidity with the Harris Tweed. Are you going to tell me why you got the tattoo of an under-achiever like this?’

‘I felt for his loss.’

That answer fizzled. I felt somewhat cheated. ‘Righto.’

8 | 八

The lights dimmed abruptly.

There was darkness, and definitely no more hot water.

We’re not talking the pitch black that greeted me after I was dead and buried, or cremated and scattered—or whatever the case may be—when I first landed, slap-bang, in that miserable place I call the Hereafter (have you dreamed up a better moniker yet?).

My fingers had stopped aching, for which I was beholden, and I was completely dressed, in a relatively comfortable seat, and heard the subdued murmur of people around me.

There was a gathering rumble of sound, a slowly advancing noise that came from what I recognized as an orchestra pit below, in front of closed stage curtains.

We were in some kind of large theatre, and although most of the lights were out, they slowly grew back, along with the sound.

‘Richard Wagner’s “Vorspiel”, the prelude of Das Rheingold—we’re listening to the low E Flat beginnings,’ said a childish voice beside me.

As my sight adjusted, I found myself face-to-face with a six-year-old. The girl peered back from beneath a cute, pageboy haircut.

‘We’re at the bottom of the Rhine,’ she said lightly. ‘The music builds slowly, to a stirring drone in E Flat major. Can you hear it?’

How a child could dissect something that was, for me at least, wonky pedestrian noise, came across disconcerting. For all I knew, she was making it up and hoodwinking the old man in the next seat.

‘Wolram, it’s me.’

‘Kohana?’

‘You were expecting Little Red Riding Hood?’

‘I haven’t the faintest idea. So, what’s afoot this time? And why the kiddie get-up?’

‘It’s early 1936.’

‘Of course it is.’

‘So, you get to meet itsy-bitsy me.’

The girl stood up, all of one hundred and ten centimetres, in a taffeta party dress and big bow, and curtsied to me. Then she grinned and sat down again.

‘Very polite of you,’ I remarked. ‘Tell me, is this where the Arthurian nonsense started?’

‘Actually, Das Rheingold isn’t about King Arthur at all. It’s the story of water-sprites in the Rhine River, some coveted gold, and assorted characters from Norse mythology.’

‘Don’t they go hand-in-hand?’

‘No! …Well, I suppose they could, if you choose to be completely ignorant.’

‘And we’re backtracking this far because you wanted to give me a better musical education?’

‘Why not?’

As Kohana kicked back, I noticed her feet didn’t come close to touching the floor.

‘To fill you in, when I was six years old, the world famous Freigedank-Dummheit Opera Company came from Dresden, to tour Japan for several performances. They were a hit. Germans were popular here in the 1930s.’

‘Likely, this had something to do with the kindred authoritarian bias.’

I looked around the theatre. The walls were gold and the ceiling had a huge chandelier, as well as a big picture of a nymph. There would have been over a thousand people there, many in Western clothes, but most in traditional Japanese garb.

‘We’re in the Teikoku Gekijo, also known as Teigeki—the Imperial Theatre in Tokyo,’ Kohana held forth in her new, disquieting child’s tone.

‘You didn’t have your Orochi tattoo at this age, did you?’

‘Wolram, I’m a little young to go getting tattoos.’

‘Well, you brought me here, true, but aren’t you also, then, too young to be allowed admittance to a prestigious event like this?’

The girl pouted. ‘I guess.’

‘Who brought you?’

‘My father. He loved opera. I used to come here every summer as a child. You know, before the war.’

‘Which war?’

She slit her eyes.

Curiosity definitely got the better of me. ‘Where is your old man?’

‘You’re sitting in his seat.’

I almost jumped out of the thing, worried I’d been reclining on some poor fellow, but there was nobody beneath me.

‘Good gosh, Kohana—don’t scare me that way. He’s not here?’

‘He’s not important.’

‘You’re desperate to hide the man from me. Why is that?’

‘Not desperate—I choose to spend no more time with him.’

‘Your drama, I suppose.’

About three minutes had past since the orchestral thrum began, and I will admit it had something rousing and zippy about it. Of course, I’d heard the music before—I just felt like playing it dopey.

The waif-like Kohana had turned away and was gazing at the nymph on the ceiling. It took another half minute for me to notice the tears on her cheeks.

‘This was the most sublime, moving music I had ever heard,’ she said, so softly I barely took in the words. ‘Beautiful, isn’t it?’

‘What is?’

‘The music.’

‘What music?’

‘The music they’re playing.’

‘Oh, yeah.’

‘To be honest, the opening four to five minutes were the best. The rest of the opera, well, I could have done without it. Straight after the performance, my father flagged down a rickshaw, we stopped by Oume-san’s okiya—and he left me there. For good. I never saw him again, but I am grateful for this parting gift.’

One thing occurred to me—where was Kohana’s sister Tomeko, in this memory? If she were taken to the geisha house at the same time, after the grand finale, wouldn’t the girl logically be here? A frumpy, middle-aged woman with far too much makeup occupied the seat next to Kohana.

That was the moment I remembered something.

Another concert, another six-year-old. Not Wagner. What were they playing? Mozart? No, Tchaikovsky, something from The Nutcracker.

Corinne beside me, watching and listening in awe. She adored the ballet, even if she would never be able to dance.

Me, checking text-messages, bored senseless. Ignoring the girl as much as I did the music. Her sad expression, when I finally found the time to take a look.

I brushed it off and started texting again.

9 | 九

‘1939, I think. Looks like a spiffy spring day for Tokyo.’

Kohana breathed out loudly.

‘You don’t sound so happy about it.’

‘Oh, I am, I am. But it’s a mixed blessing.’

I followed her into a small garden, with high wooden walls on all four sides. There was a cautiously dripping bamboo doohickey in one corner, and the elderly woman of the house stretched back on a recliner.

Music came from somewhere inside the house.

‘It’s “Natsukashi No Bolero” by Ichiro Fujiyama,’ my companion said. ‘Oume-san’s favourite record at the time. She played it over and over, and wore the thing out.’

‘Sounds like a hoot.’

‘What actually is a hoot?’

‘I’m not sure. Fun?’

‘Pfff.’

Before me was the rather storied mama-san, Oume. Sadly, I was not impressed. The woman appeared to be a skinny bag of bones aged somewhere from fifty to ninety—it was impossible to tell how old—and she was not an attractive sight.

Her face was crisscrossed by lines, and her scraggly hair a mix of white, grey and shreds of black. The woman’s teeth were crooked and the mouth lopsided. But those hooded eyes twinkled with a solid combination of good humour and intelligence.

The woman was reading from a novel that had on its cover two roughly painted soldiers, sharing a cigarette, on a plain yellow background. Also gazing at that image was a nearby young girl with a long ponytail, seated on the ground next to the old biddy.

‘Me. About nine, I’m fairly sure. I remember this. Oume-san, in the back garden of the Paulownia Tree, with a pipe and this book. She sat like a queen in that flimsy chaise longue you see, next to the tree stump.’

‘Queen’ wasn’t the word I was clutching for.

‘What are you reading?’ the girl asked.

‘Mugi to Heitai. Wheat and Soldiers,’ said the old lady, in a gravelly tone. ‘It’s by a writer I like, Hino Ashihei, a novel that touches upon the evils of war. There should be more of this, but with the new edicts coming through, and this rampant government militarism, soon all we’ll be allowed to read about will be the beauty of bloodshed. In manga form, with silly pictures.’

The old woman set down her book, took a pinch of shredded tobacco, and filled her long-stemmed pipe.

‘Never believe what these people ram down our throats, Kohana-chan. The government is roosted by piman.’

‘Capsicums?’ I queried.

‘What’s inside a capsicum?’

‘Very little.’

‘There you go. Picture their heads as little green peppers.’

‘Oh, I see. A nice touch.’ That sorted, I returned my wandering attention to the lady on the couch.

‘I loved this old tree,’ she was saying as she patted the amputated stump beside her. ‘It was ancient like me, a real survivor. But it got too big and the neighbours complained, and we had to chop it down. One of the saddest things I’ve ever done. But there’s a lesson in there for you, little one. Never let yourself get too big.’

I leaned forward. ‘Er—I hate to break the moment, but was she talking up your weight, or your possible future success?’

‘I was never quite sure,’ Kohana admitted. ‘I like to believe it was a more philosophical moment and she was referring to the latter. I’d hate to think the moment was lost on an observation that I might be getting chubby.’

She turned full circle in the yard, and sighed.

‘I also remember the day our father brought us here.’

Oume, and the girl, and the recliner vanished.

The trees and plants around us back-pedalled three seasons in as many seconds, and a tall tree stood where the stump had once been. It was wrapped in summer foliage.

I could make out chatter inside the house—a man’s voice, deep and gruff, and an elderly woman’s growl I recognized as Oume’s.

‘I want to be rid of the one, I tell you, only this one,’ the man’s voice said, annoyed. ‘The other is not for sale.’

‘I’ll take them both.’ That was Oume. She sounded stubborn—one of those people with whom you don’t want to do business. ‘They’re perfect bookends. Individually, I’d make a quarter of the profit that, together, they will bring. I’m sorry, but that is my single condition. Both, or neither.’

I stole a look through the open window, into the gloom of the house, but could make out nobody.

‘Are they discussing what I believe they’re discussing?’

‘It’s obvious what’s happening,’ Kohana muttered, as she leaned against the wall. She looked up and fingered the old wooden boards there. ‘My father wanted to offload me to an okiya he frequented. I think he was sick and tired of the constant reminder of his dead spouse. But Oume-san refused to take just one—she wanted the two of us. She may not have been a terribly astute businesswoman, but she could see a pot of gold when it appeared in front of her, and my father folded quickly.’

A marginally younger-looking Oume emerged from the doorway, leading two children by their hands. She seated them on a bench and gazed at them.

They were beautiful girls, dressed identically with short bob hairstyles and taffeta dresses. I recognized them from Kohana’s look at the opera. Bookends indeed.

One of the pair had a blue and yellow flower tucked behind her right ear.

‘Ne m’oubliez pas,’ Kohana said in a soft voice. ‘Otherwise known as a forget-me-not. We call them wasurenagusa in Japanese. Same meaning. When I was a child, I adored flowers.’

Oume cleared her throat, not that it made her voice any prettier.

‘So, now we are a family,’ she said, as she squatted in front of both charges. ‘Shall we get acquainted? What are your names

?’

‘My name is Tomeko,’ said one of the two, the one without the flower, in a small, shy voice.

‘A pleasant enough name. And yours, my dear?’

The other girl bobbed low. ‘I’m Akuma.’

Oume whistled. ‘Oh, no, no, no, that name won’t do. Not at all. It will scare potential customers half to death.’

The woman studied the girl for a few moments, and it seemed her scrutiny came to rest on the flower behind the ear.

‘I think we’ll call you Kohana. What do you say?’

10 | 十

‘A bombing raid?’

I shook my head to clear it of unnecessary nonsense. Hadn’t I been here before? Déjà vu, and all that jazz? I felt like I’d been kicked in the behind.

Minus the couch, this time around.

I was nestled on a stool, on a dark footpath, next to a wooden dwelling I recognized, despite the poor light. Not Kohana’s hovel—her okiya. Oume-san’s place. No doubt the lantern aided in identification.

‘Not any garden-variety bombing raid, my sweet,’ Kohana was saying as she walked around me with small steps, surprisingly steady on precarious-looking geta. Yes, she was the almost fully-grown geisha again.

‘Hangyoku,’ she reminded me, suddenly very close to my ear. I nearly perfected the jumping-out-of-one’s-skin manoeuvre. She’d covered ten feet in less than a second, clogs or no clogs.

‘I get you,’ I assured her, tense.

I was also annoyed, because I could make out those bees again. It was an irritating sound. Would I be allowed no peace? Give me Wagner any day.

Then I made up my mind to do something.

‘Do you mind if I explore? I know this street well enough, though last time I was comfy in a couch. The stool is a bit hard.’

I stood up, stretched my back, and eyed off an alley three doors down. I don’t know about you, but I’ve always had a fascination for lanes—something that stems from growing up in Melbourne, where there are fascinating laneways aplenty.

‘No.’ Kohana’s arm stopped me.

‘Just a brisk walk.’

‘Not now.’ She sounded adamant. ‘Focus. Listen. You hear that?’

‘Yes, yes, the bees, or the Allied planes, are whatever they are.’

The Condimental Op

The Condimental Op Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa?

Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa? 100 Years of Vicissitude

100 Years of Vicissitude